From time to time, I circle back to the question of the balance of deficits. In my mind, as our economy goes through whatever the “Trump Transition” is, the biggest risk to the bond markets is not from some fear about whether the Treasury will default or whether the US dollar will cease to be the world’s currency of choice for reserves (neither of which I think is going to happen any time soon) but that large secular changes in the balances of savings and dollar demand could lead to outsized moves in interest rates.

First, let me remind you that the deficits are all intertwined. When the US Federal Government runs a deficit and borrows money, they have to get it from people/entities that have saved that money. One place that the government bond salesmen know they can turn to is non-US investors, who are in possession of those dollars because the US runs a large trade deficit with most other countries. When we run a trade deficit, it means we are importing more stuff than we are exporting or, equivalently, we are exporting more dollars than we are importing. Those dollars are pretty useless except to buy things that are dollar-denominated. By construction, we know that the new owners of dollars aren’t buying goods, because if they did there wouldn’t be a deficit; the main other thing they buy are securities or real property.

So if you don’t want other countries buying US stocks, buildings, and farmland, run a big trade surplus and they won’t have the dollars to do it.

It’s a good thing they have all of those dollars, because the Federal government needs them! The federal deficit needs to be funded by those foreign dollars, or by domestic savings (banks, individuals, companies, e.g.), or by the central bank buying up those bonds. And that’s pretty much it. Over time, the trade balance plus the budget balance plus the central bank balance plus private savings equals zero, more or less. During COVID, the massive expansion of the federal deficit was only possible because the Fed bought about the same number of bonds as the government sold. Had they not, interest rates would have risen precipitously because private savers would have had to be induced to put those dollars into bonds.

(Or, the government would give incentives for banks to hold more govvies, say by exempting them from the SLR. Not that such a thing would ever happen!)

Let’s pivot this then back to the Trump Transition. The stated goal of the Administration was to lower the trade deficit a lot, lower the budget deficit a lot, and lower interest rates. That all makes sense and is internally consistent. It could happen that way, if all of it happens that way.

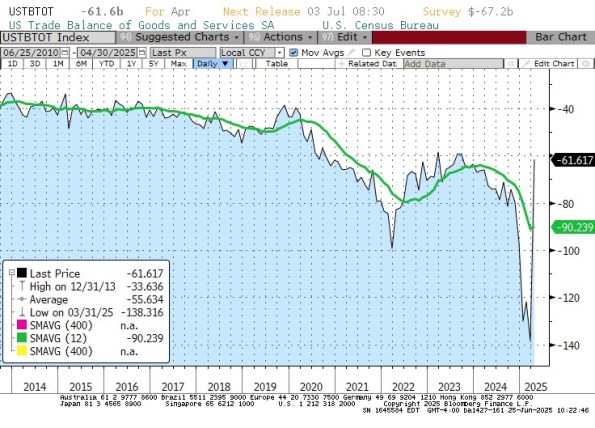

What if, though, the President’s team makes more progress on one front than on the other? Early returns on the tariff front seem to imply that the US will face a smaller trade deficit going forward. Now, the latest spike higher (smaller deficit) here is at least partly and maybe mostly due to a ‘payback’ of the pre-tariff front-running that led to massive deficits in the prior three months. But it should not surprise us that increasing tariffs should cause the trade deficit to decline. That is, after all, sort of the point.

If we concede that the trade deficit is actually heading back towards some better semblance of balance, then that’s plank 1 of the Trump agenda. That will supply fewer dollars to cover the federal budget deficit, though. As long as the federal budget gets into something closer to balance…

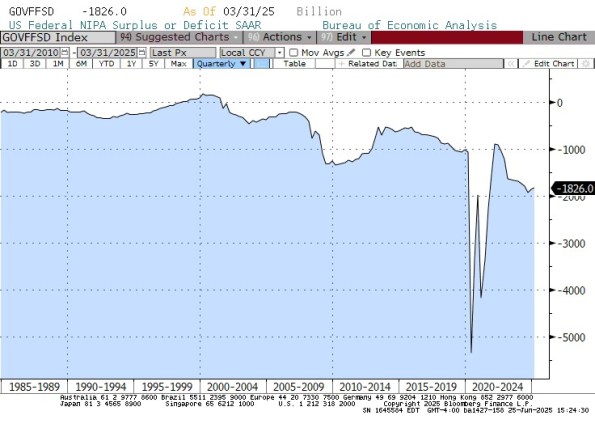

That was the promise of DOGE, and of the revenues from tariffs. The latter will indeed be yuge, and will help balancing the budget. Or it would, if we weren’t about to run an even bigger deficit with the Big Beautiful Bill soon passing into law. The trailing-twelve-month budget deficit is just less than $2 trillion, which was a number we never even sniffed prior to COVID. So that’s the demand for savings: the feds look like they’re going to keep on spending more than they take in.

Unlike during COVID, too, the Fed is now letting its balance sheet shrink. No help there.

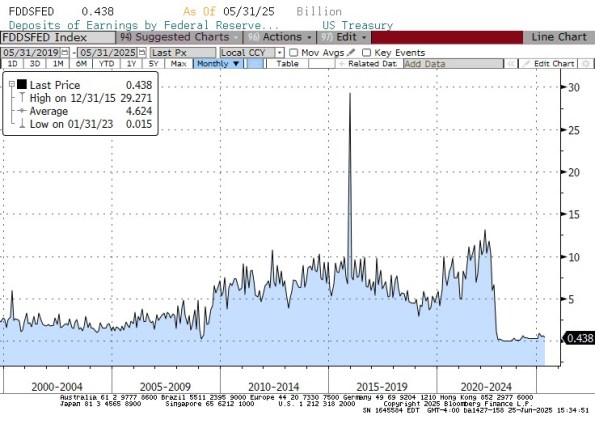

Now, there is also a movement in Congress to pass legislation preventing the Fed from paying interest on the reserves that banks hold at the Fed. For decades, the way the Fed managed the money supply was to adjust the quantity of reserves, which rationed credit and caused the price of credit (interest rates) to move as well. But it was the rationing of credit, not changing the price, that affected the money supply. Beginning with the Global Financial Crisis, the Fed flooded extra reserves into the system, forcibly deleveraging banks (look at that chart above again) – but, since that would also crush bank earnings, they started paying interest on reserves (IOR). Since, if banks were not being paid to hold reserves, they would hold as little as they could, the Fed had to pay interest or the excess of reserves in the overnight market would cause interest rates to always be zero. So the Fed started to manage the price of credit, rather than its quantity. The central bank fully intends to always hold way more in securities and therefore force way more reserves into the banks, going forward – but has gradually been reducing its portfolio securities. As I said, no help there.

If Congress succeeds in preventing the payment of IOR – and the politics on this looks good since the Fed now runs operating deficits, so that it is basically paying banks interest with taxpayer dollars (see chart below…Fed remits to the Treasury have dried up completely), then as I said above banks will try to hold fewer reserves and overnight interest rates will drop as banks compete to lend their excess reserves at anything above zero, unless (a) the fed increases the reserves banks are required to hold (really unlikely) or (b) the fed makes reserves scarce so some banks will have to buy them and some will sell them (the old way) (also really unlikely). In neither case does the Fed expand the balance sheet as a first intention, so unless we get another crisis the expansion of the Fed balance sheet is unlikely in my view.

So that leaves private savings. If the trade deficit declines and the budget balance doesn’t move significantly towards balance, then interest rates will have to rise, potentially a lot. I think the President’s stated plan makes very good economic sense. I just wonder if it’s going to be derailed by the desire to keep the Federal spend going.