When China’s massive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched in 2013, I was a great admirer. On paper, it was—and remains—the most ambitious infrastructure project in human history, a modern-day Silk Road stretching from Asia to Europe, Africa and the Americas.

As the years have passed, however, I’ve come to see the BRI as a Trojan Horse, quietly rolling through emerging markets while Washington looks elsewhere. That’s especially true in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

Today, I believe that unless the U.S. can offer LAC economies credible, long-term alternatives on infrastructure, technology, defense and more, it risks giving up influence in its own backyard, for decades to come.

Chancay Port: A New Era of Chinese Control

In November of last year, Chinese President Xi Jinping was in Peru, cutting the ribbon on the $1.3 billion Chancay deep-water port. As the first “smart port” in South America—boasting a network of highways, railways, data cables and power grids—Chancay was built by Chinese state-owned shipping giant COSCO, which also operates the property.

Beijing claims the port will generate 8,000 jobs and slash shipping costs between China and South America by 20%. It will also cut roughly 10 days off transportation times, giving China an edge in trade and supply chains across the hemisphere.

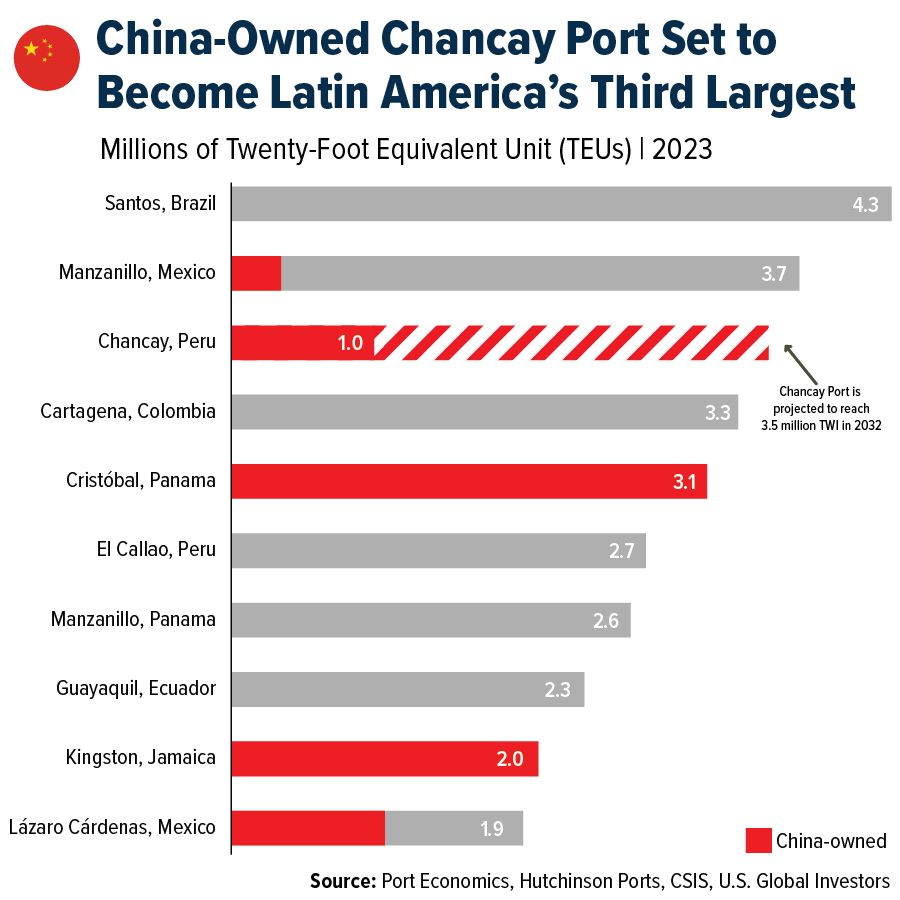

The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) estimates that, once fully expanded, Chancay could handle 3.5 million containers per year, potentially making it the third-largest port in Latin America, and the largest controlled entirely by a Chinese state-owned enterprise.

The CSIS, in fact, has identified 37 seaports in LAC with ties to Chinese companies. For comparison’s sake, the U.S. does not operate any ports in the region.

The CSIS, in fact, has identified 37 seaports in LAC with ties to Chinese companies. For comparison’s sake, the U.S. does not operate any ports in the region.

China’s Influence Reaches Every Corner of the Continent

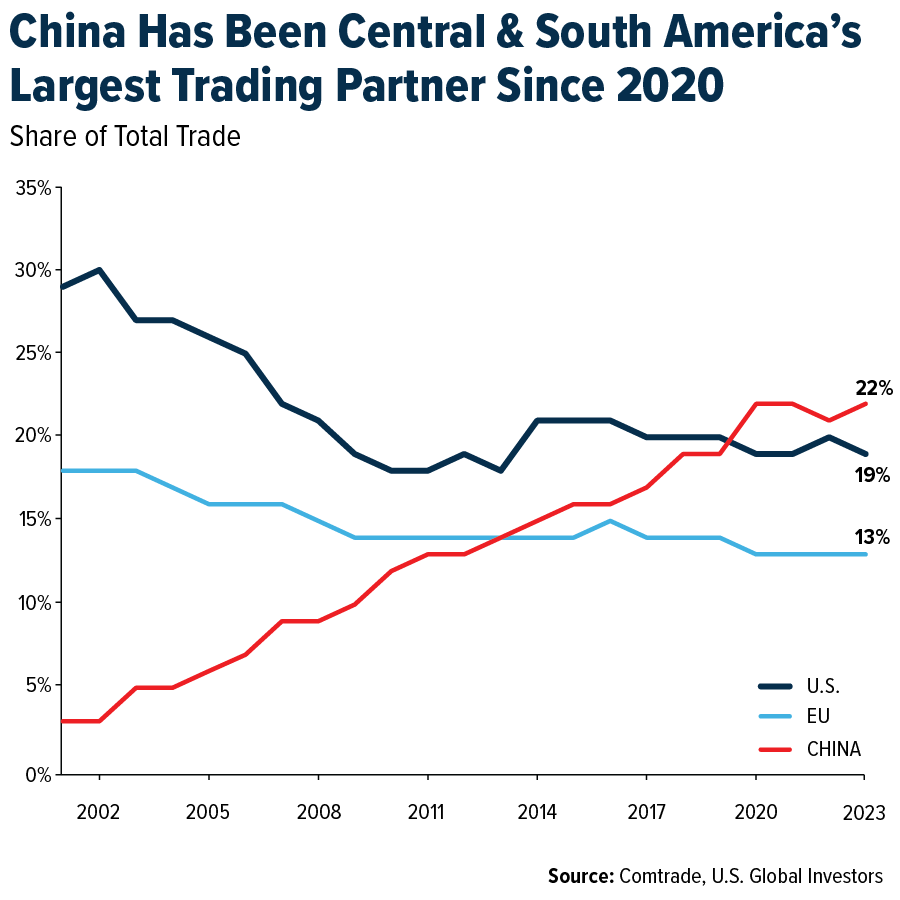

How did we get here? After joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, China’s trade with Latin America grew an average of 31% a year for approximately the next decade. In 2024, bilateral trade between the two regions hit $518 billion, overtaking the U.S. as South America’s top trading partner. Analysts expect that figure to reach $700 billion by 2035. China is the largest buyer of Argentina’s lithium, Venezuela’s crude and Brazil’s soybeans and iron ore.

The world’s second-largest economy is also the main builder of infrastructure, from metro stations in Bogotá and Mexico City to hydroelectric dams in Ecuador. In just two decades, Beijing has financed over $286 billion in Latin American projects, approaching its total investment in Africa.

The world’s second-largest economy is also the main builder of infrastructure, from metro stations in Bogotá and Mexico City to hydroelectric dams in Ecuador. In just two decades, Beijing has financed over $286 billion in Latin American projects, approaching its total investment in Africa.

One such example—besides the Chancay seaport—is Chile’s new China-Chile Express submarine cable, which aims to link the Pacific coast directly to Hong Kong. Some experts warn, however, that the project could exposure the continent to China’s 2017 Cybersecurity Law, which could compel companies to cooperate with Chinese state intelligence.

$180 Billion-Per-Year Infrastructure Spending Gap

For the U.S., I believe this is as much a crisis of neglect as it is of strategy.

While Washington has focused more on counterterrorism and short-term aid programs in LAC, China has played the long game, financing ports, railways and power grids. This in turn has helped foster goodwill and shaped its relationship with the region for decades and perhaps generations to come.

Between 2000 and 2021, Beijing financed an estimated $1.5 trillion worth of overseas development projects, 85% of them as loans rather than aid, making the country the largest official creditor to emerging markets.

In contrast, total U.S. foreign assistance, which has averaged around 1% of the federal budget, has barely kept pace with inflation (and, indeed, has been gutted by the second Trump administration.)

This has allowed China to present itself as the only offer on the table. Latin America’s infrastructure deficit is enormous at an estimated $180 billion a year through 2030, according to the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). As the Heritage Foundation’s Michael Cummingham warned last year: “It’s not like Washington gave [Latin America] a better alternative… The region’s demand for infrastructure makes it ripe for the picking.”

China’s Military and Security Presence

Trade is only part of the story. China is expanding its military and security presence in the region too. China now operates or co-manages at least eight ground stations in Latin America, including deep-space tracking centers in Argentina, Venezuela, Bolivia, Chile and Brazil. These stations provide the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) with global telemetry coverage and real-time spatial data.

Under the Global Security Initiative (GSI), proposed by Xi in 2022, Beijing has shifted toward domestic security, supplying tactical gear and facial-recognition systems to police forces from Panama to Ecuador. Huawei-built “Safe City” networks can now be found in more than 35 Latin American municipalities, integrating thousands of cameras and emergency centers under Chinese-managed software.

Even the BRI blurs the line between civilian and military use. Peru’s Chancay Port could serve future naval logistics for the PLA, while the Espacio Lejano space station in Neuquén, Argentina, already supports China’s hypersonic and satellite-tracking capabilities.

The Yuan’s Ascent

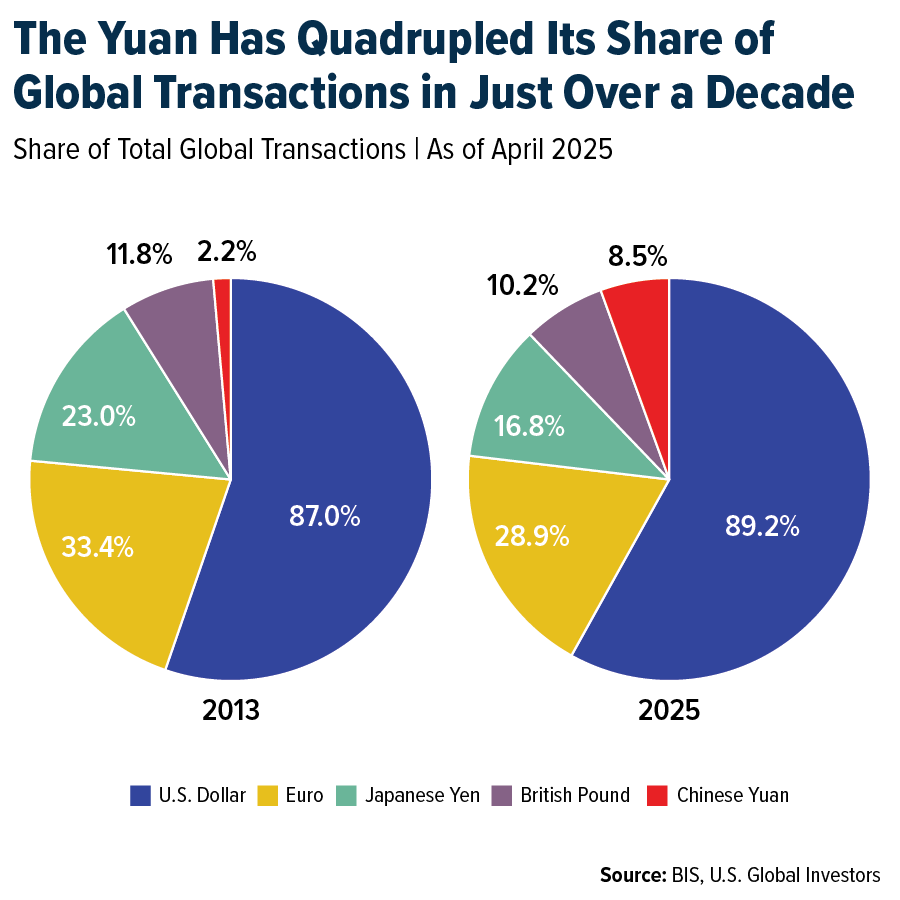

All of this coincides with the Chinese yuan’s ascent as a foreign reserve asset and settlement currency. According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the yuan now accounts for 8.5% of global transactions, up from 7% just three years ago and closing in on the British pound’s 10.2% share. The U.S. dollar remains the global leader by far, representing nearly 90% of all transactions, but the yuan has made impressive strides, quadrupling its share of total transactions since 2013.

As The Economist put it, China’s leader’s “sense an epic opportunity.” Fiscal deficits and political gridlock in the U.S. have shaken confidence in the greenback, which had its worst start to a year since 1973; meanwhile, Beijing is pushing yuan-denominated trade through its Belt and Road partners.

A Lasting Foothold in the Global South

China’s strategy goes far beyond infrastructure projects, of course. It seeks to gain a lasting foothold in the Global South, with the BRI as its Trojan Horse.

Last week, Beijing announced it would further tighten export rules on rare earths, minerals that are vital to semiconductors and defense systems. This prompted President Trump to threaten sweeping new tariffs.

At the same time, the People’s Bank of China logged its 11th consecutive month of gold purchases, extending its push to de-dollarize and insulate its economy from U.S. sanctions and currency shocks.

Taken together, these moves reveal China’s imperial ambitions, which include a network of ports, power grids and rails—all designed not only to move goods but also exert influence.

***

All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor. By clicking the links above, you will be directed to a third-party website. U.S. Global Investors does not endorse all information supplied by these websites and is not responsible for their content.