In the course of this inflation cycle – and I do think this is a cycle, and not necessarily a one-off, although the subsequent peaks may not surpass this year’s peak in Median for some years – the typical topic has of course been the level of inflation, and/or its acceleration or deceleration (not to mention, many uneducated suppositions about the cause, which we know good and well boils down to profligate spending and unprecedented provision of money).

I’ve also written and talked about the oft-overlooked fact that when inflation rises for some time above about 2.5%-3%, stocks, and bonds become correlated rather than inversely correlated, and this has a significant effect on portfolio risk that insightful investment managers will take into account.

What I haven’t written about much is the fact that problems are also caused by the volatility of inflation. While this tends to go hand-in-hand with higher inflation, the problems caused by inflation’s volatility are somewhat different than those caused by its level.

CPI Level and Volume

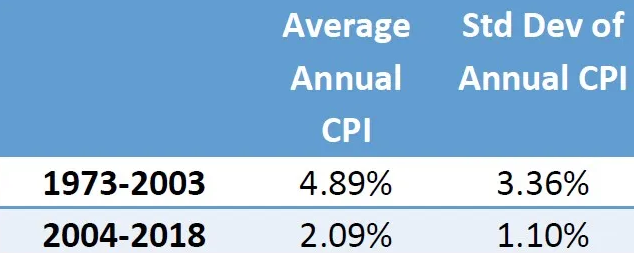

The current episode follows a 15-year period during which inflation was both low and stable. The thirty years prior to that, from 1973-2003, the level of inflation was a bit more than twice the 2004-2018 period average but the volatility of inflation was tripled.

The importance of inflation volatility is that it operates on inflation expectations in a very different way than the inflation level does. (We know that inflation expectations do not have the center-stage role in ‘anchoring inflation’ that previously-discredited theory claimed it did, but I do think there is a psychological tendency that adds some inertia to inflation by affecting businesses’ beliefs about how easy it will be to increase prices.) Inflation volatility tends to increase consumers’ perceptions of inflation through behavioral tendencies toward loss aversion and attribution bias. But it has other effects as well.

Quantitatively, higher variance makes it harder to reject the null hypothesis that inflation is staying high; an uncertain worker is therefore less likely to accept a lower wage that may not suffice and a business is less likely to hold the line on prices that may be continuing to rise elsewhere. When you don’t know the true competitive pricing situation, both businesses and their employees are likely to err on the conservative side. This also gives momentum to inflation.

Higher inflation volatility is what causes the inflation factor to carry more weight in the minds of consumers and investors, which in turn is what induces the aforementioned positive correlation between stocks and bonds. When inflation is low (but more importantly stable), the importance of inflation to investors is also low and variations in inflation are given less weight than variations in growth. Since stocks and bonds behave similarly with respect to inflation but inversely with respect to economic growth, the dampening of the inflation factor is the reason that stocks and bonds are inversely-correlated in low-and-stable inflation regimes.

Also, although investors seem not to incorporate this understanding into prices, higher inflation volatility should increase the value of a “tail outcome” in inflation and increase the value of holding that option by being long breakevens, or long TIPS instead of nominal bonds. That is, when inflation isn’t going to vary too much, then it’s hard to win big by owning TIPS over nominals; but if inflation varies a lot, then there should be a fairly large premium built into breakevens since you’d much rather be long them (and long that tail) than short them (and short the tail). However, as I said, this seems not to actually be incorporated in inflation markets, which trade far below the level they ought to if inflation tails have even a small value.

So, How Volatile Has Inflation Been?

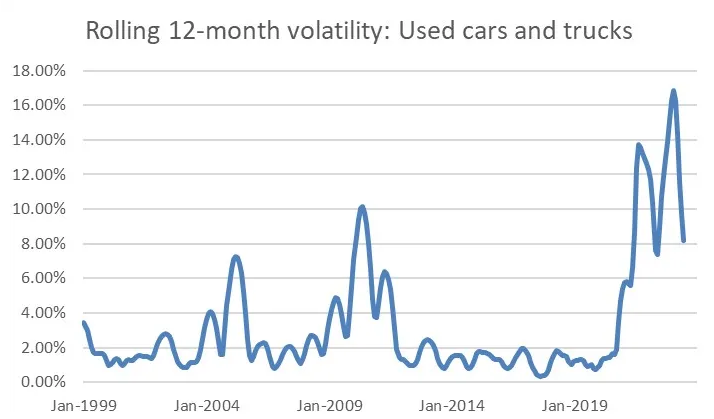

When I started thinking about this blog post, I was originally going to point out that the volatility of Used Car CPI is so much higher than it used to be. We almost never spent a lot of time thinking about how much Used Cars would add or subtract from core. Here is a chart of the rolling 12-month volatility of y/y Used Cars CPI.

Not surprisingly, the volatility of CPI for Used Cars and Trucks reached nearly double the level it did in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis when the “cash for clunkers” program and the destruction wrought by Hurricane Katrina both had major impacts on the market for used cars. But it goes beyond that.

The unusual volatility of the food and beverages group, partly as a result of the war in Ukraine and the spikes in fertilizer prices, has been documented previously. It seems to be receding but remains quite high historically.

Heck, let’s look at three of my ‘Four Pieces’ (leaving aside energy). Here’s Core Goods.

Even though the level of core goods inflation has come way back down, the volatility of core goods means that consumers can’t get terribly comfortable with prices (nor can producers).

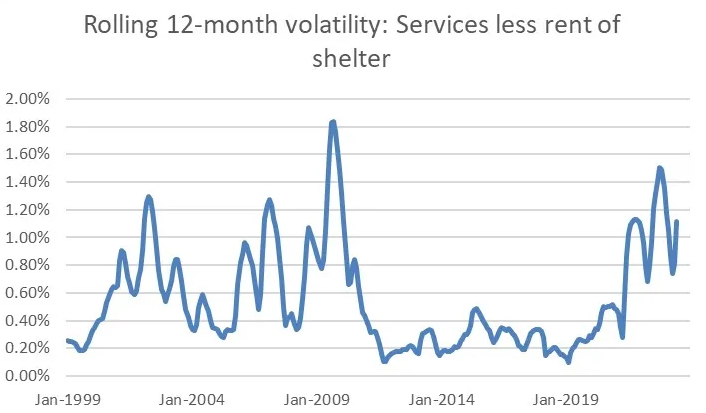

How about ‘supercore’?

This is also high, but the interesting part is how to tame it had been for most of the post-GFC period. Remembering that this is the category where the wage-price feedback loop is felt most strongly, I think this says something about the flaccidity of labor power during that decade. Well, that’s back – and perhaps we’ve re-entered an extended period of volatility in that group?

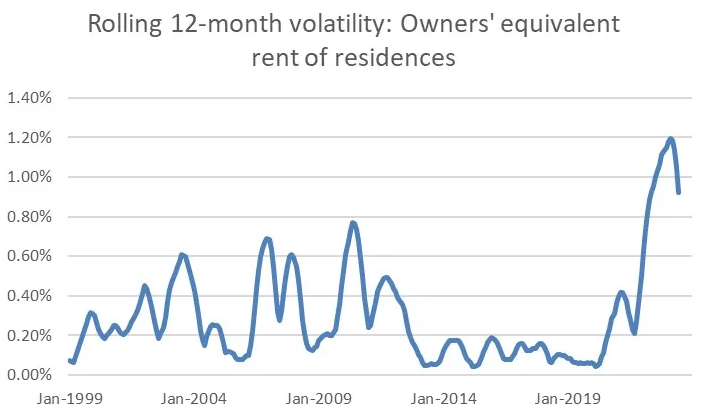

Here is the volatility of Owners’ Equivalent Rent (which looks about the same as Primary Rents, for what it’s worth, so I didn’t feel I needed to show them both).

Not as terrible as I would have thought, although to be fair this is typically a less volatile category anyway. Again, though, look at the amazingly boring period post-GFC. (As an aside, that’s when a certain inflation specialist was trying to get attention for Enduring Investments.)

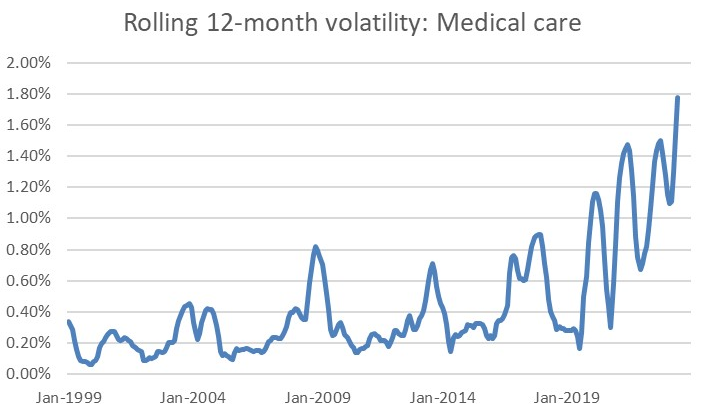

In a second I’ll show all-items CPI, but first let’s look at Medical Care.

This is the only category of the ones I’ve shown where volatility is still increasing. That’s largely because of health insurance, which, as I’ve documented/complained about for some time has endured one of the most massive swings in any imputed category. That will not plummet soon, though, since in October, the Health Insurance drag of -4% or so annualized will reverse to +1% or so.

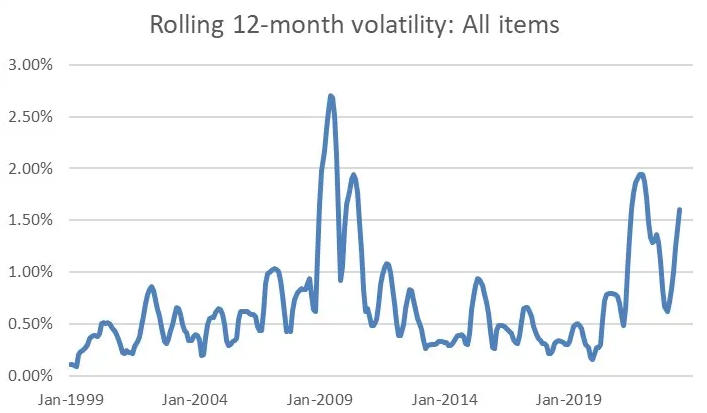

Last but not least, here is the headline CPI’s volatility.

I will just say that it is a good thing that inflation dealers no longer really trade inflation options. Because, if they did, they not only would generally be short a whole lot of in-the-money inflation cap delta in the book but also would be short a bunch of vega too, and implied vol would probably be a lot higher. But the importance of this picture is that while headline inflation has been receding (largely due to energy) and inflation has been dropping too (not insignificantly due to Health Insurance and Used Cars), the volatility of inflation does not yet look like it’s calming down in a decisive way.

Until it does, I think it would be cavalier to assume that we are heading back to the low-and-stable inflation regime, even if the last few months out-turns for CPI have been agreeable. Volatility, and not just the level of inflation, matters.