The Federal Reserve is widely expected to start cutting interest rates at the Sep. 18 FOMC meeting, but the debate is turning to how far the central bank will trim its policy rate once the easing begins? A key part of the answer will be determined by how much the neutral rate has increased, if at all, in recent years.

The so-called neutral rate is the optimal rate at which the economy grows through time without raising inflation. Unfortunately, the true neutral rate is unobservable and so economists can only estimate it with models.

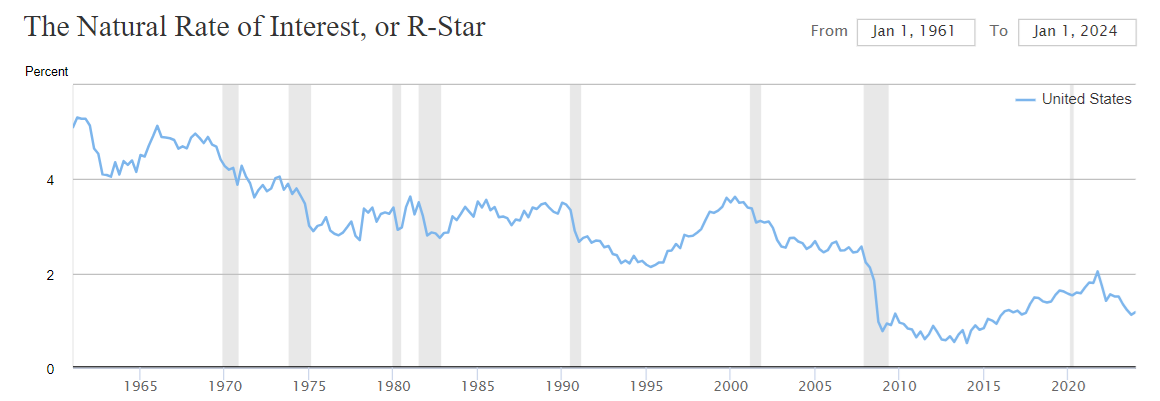

One model run by the New York Federal Reserve shows that the neutral rate (a.k.a. the natural rate or R-star) has fallen and is roughly 1.2% as of this year’s first quarter. Although that’s up from a decade ago, it’s still down from the roughly 3% level that prevailed in the 1980s and 1990s.

But estimating the neutral rate is tricky and there are wide-ranging debates about the best approach. Not surprisingly, estimates vary, in some cases widely.

Recent surveys indicate that some economists think that the neutral rate has increased. The Bank of International Settlements recent advised that “the recent reemergence of upside inflation risks inducing a tighter monetary policy stance going forward may have pushed at least perceptions of r* higher.”

Meanwhile, Reuters reported in May:

A New York Fed survey of major banks ahead of the March meeting found dealers estimating a longer-run rate of nearly 3%, up from 2.5% the prior March.

Analysts at TD Securities told clients in a recent note, “we continue to assume that the long-run nominal neutral rate is now likely 50 basis points higher at 2.75%-3.00%, but can’t discount a somewhat higher level closer to 3.50%.” And the San Francisco Fed said in a report its in-house view on the longer-run rate stands at 2.75%.

The stakes are high in this technical debate for the future path of monetary policy. If the neutral rate has increased, that will probably limit how much the Fed can cut.

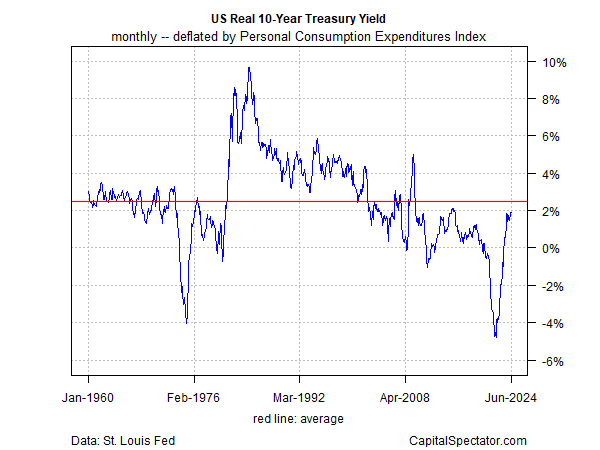

Although several factors go into estimating the neutral rate, one rough estimate for gauging the directional bias is the real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. On that front, there’s been a hefty upside shift in recent years, as the chart below indicates.

It’s premature to conclude that the natural rate of interest has materially increased, but to the extent that a sharp increase in real rates is a factor – and it is – then it’s fair to assume that Fed’s capacity for cutting rates may be narrower than recently assumed.

“If they’re gonna do two [cuts] this year, they’re effectively going to be at neutral by the end of the year,” says Jim Bianco of Bianco Research. “Given the strength of the economy, I don’t think it’s warranted.”