After years of zero interest rates, such an abrupt tightening is bound to break something.

The main questions are: what, when, and where does something break?

When rates are low credit is cheap and so financial actors tend to lever up more aggressively. Debt levels increase and so does the coverage of government debt.

Yet the reality is that governments are the issuers of fiat money and therefore they can always nominally meet their obligations by issuing more debt.

That obviously has limits too: over time they depreciate the real value of the currency and relentless fiscal deficits might lead to inflation overshoots.

But my point is that governments can kick the can down the road for a long time, but you know who can’t?

You, I, and in general the private sector.

If our mortgage costs as a share of disposable income move higher we can’t print money to service our debt.

If corporate borrowing costs soar and earnings growth doesn’t dramatically improve, companies will be quickly forced to deleverage or cut costs.

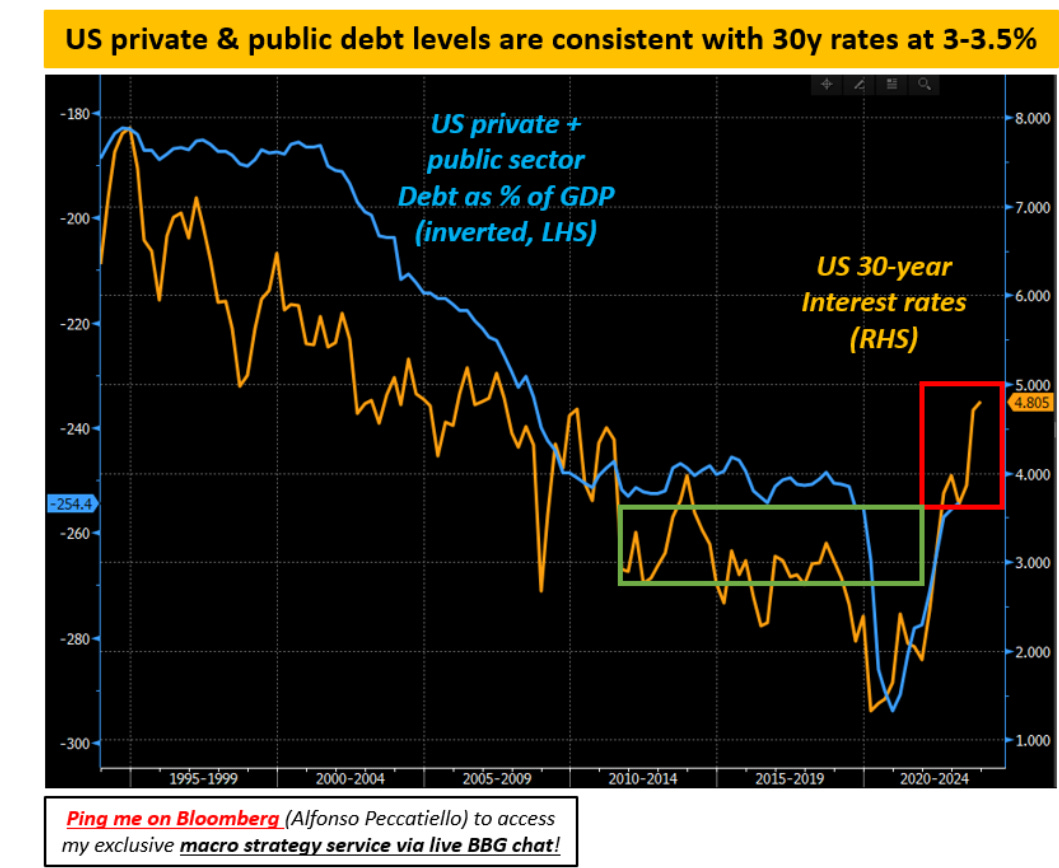

So in general it’s a good practice to keep an eye on both government and private sector debt levels (as the chart below shows the higher the total economic debt, the lower the rates must be to keep the system afloat).

Countries With High Private Debts Are More Vulnerable to Economic Shocks

During macro shocks countries with high and rising private debt levels are more vulnerable than countries with high public debt levels.

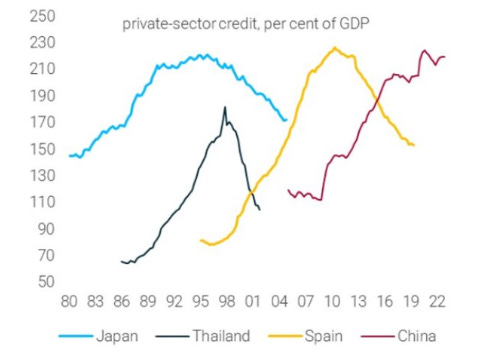

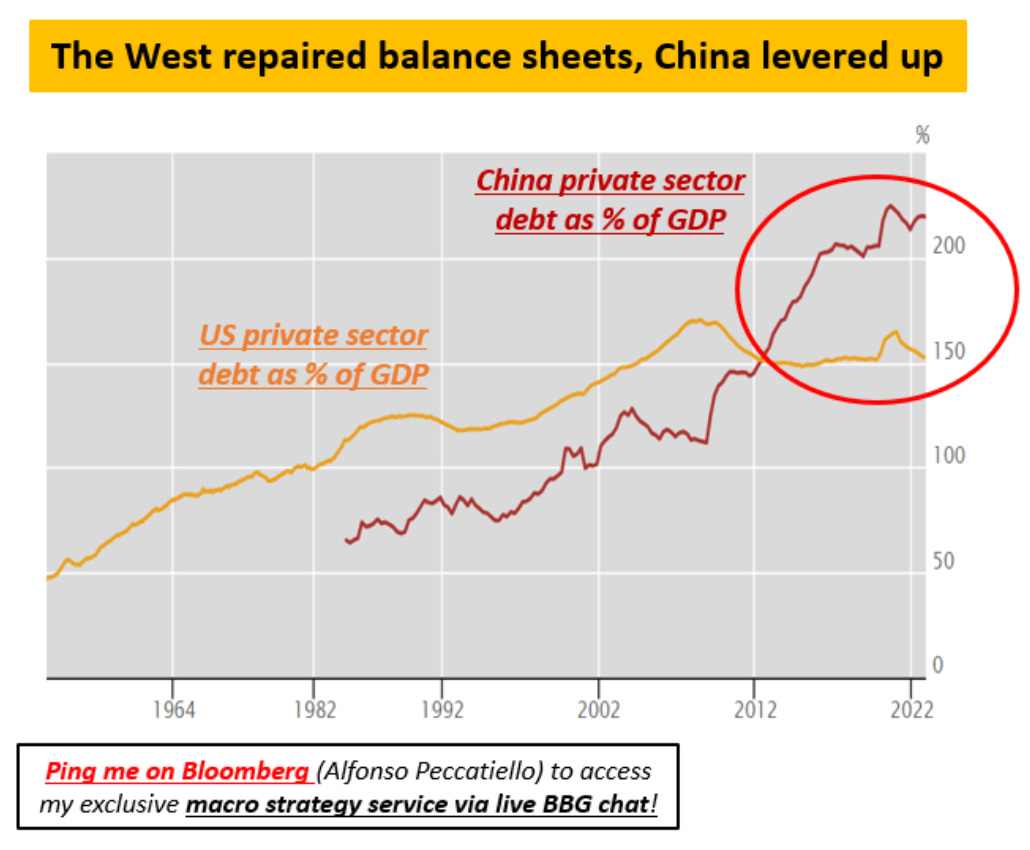

History shows that’s indeed the case: look at this great chart from Dario Perkins.

Private Sector Credit vs % of GDP

Japan’s real estate crisis 1990s

Asian tiger’s crisis late 1990s

Spain’s housing crisis early 2010s

China now?

All these episodes had one thing in common: private sector debt was too high and it was rising too rapidly.

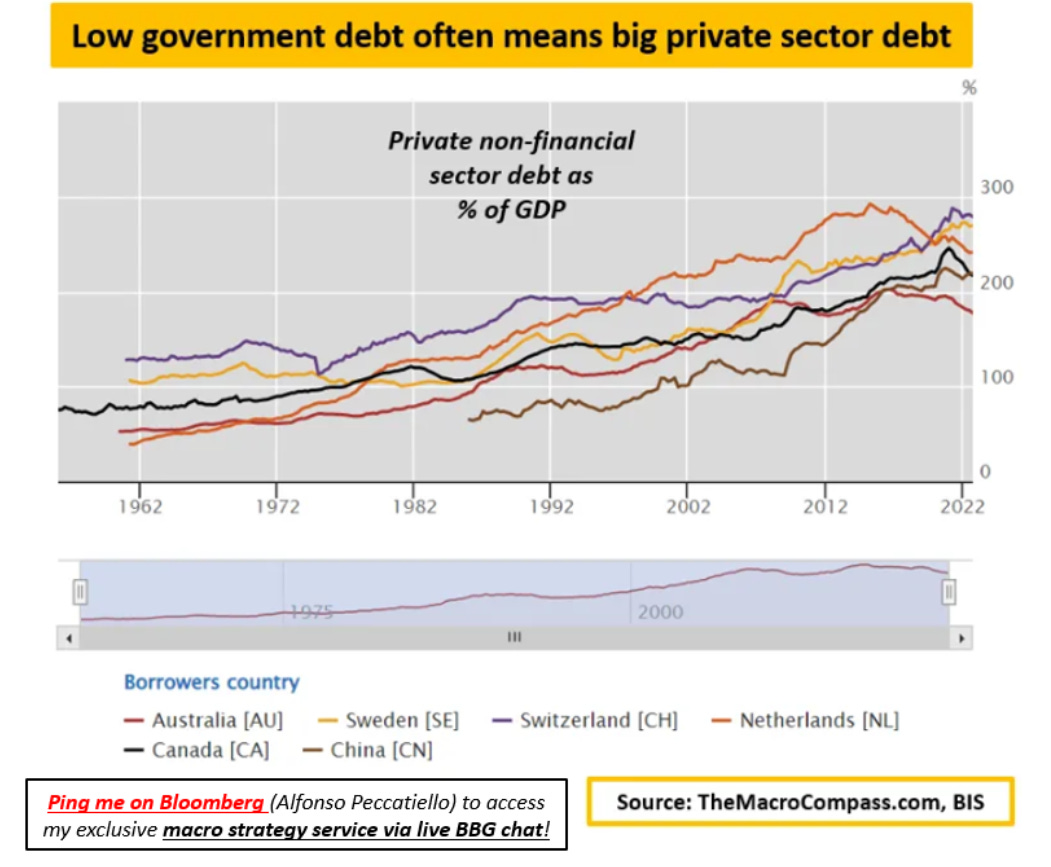

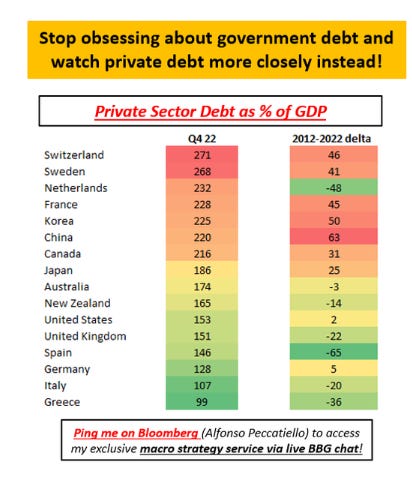

Funnily enough, the obsession with government debt levels skews the vulnerability assessment toward the ”wrong” countries.

Countries that keep deficits super contained starve the private sector of fresh resources and so households and corporations go and lever up privately.

Take China: their official government debt levels are very contained but behind the curtain, they have been aggressively leveraging up their private sector.

And if you do that too fast in an unproductive way, problems tend to occur.

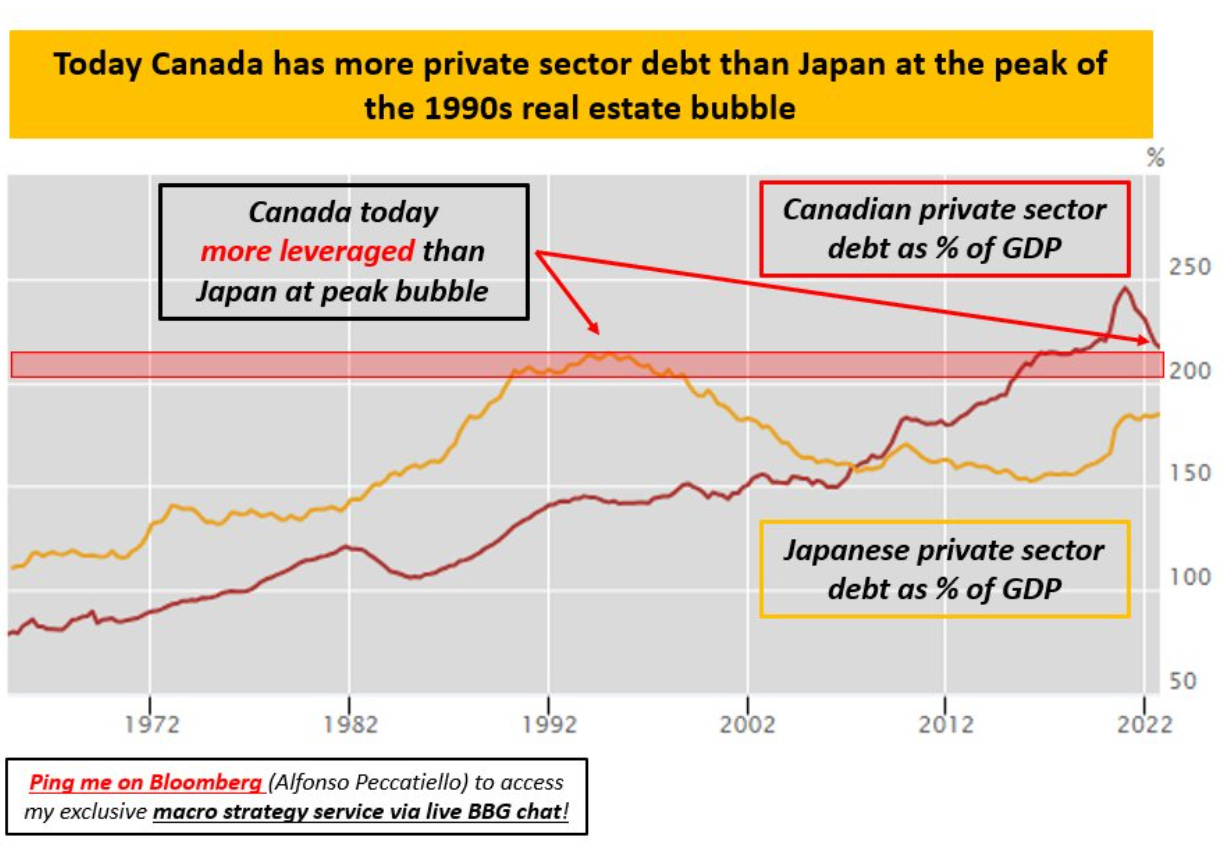

Or take Canada which has made a large use of real estate debt to spur a domestic wealth effect.

Today Canada is running a higher private sector debt/GDP than Japan did just before the implosion of their own real estate market in the 90s.

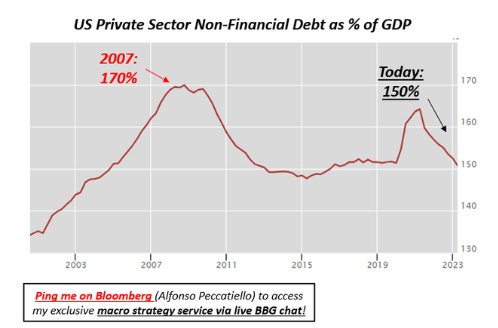

Instead, if you have a look at the US you’ll find that their private sector non-financial debt as % of GDP today is 20 percentage points lower than in 2007.

While mainstream media commentators obsess about US government debt despite the United States enjoying the privilege of issuing the reserve currency of the world, private sector leverage trends in the US show a relatively benign picture if compared to other countries around the world.

US Private Sector Non-Financial Debt

What countries score the worst by this metric, you ask?

This table can help you quickly assess in which countries private sector debt is too high and it’s been rising too fast over the last 10 years.

Private Sector Debt as GDP

Now, obviously, levels and rate of change in private sector debt are not the only variables to consider when assessing when/where/what will break in macro.

We also need to consider other fundamentals, the nature of the private sector debt market (floating or fixed rate, short-term or long-term), refinancing cliffs, and many other variables.

Hence this was just the appetizer of my investigation into ‘‘what will break in macro’’.

The good news though is that I will be serving you the entire menu soon.

***

This article was originally published on The Macro Compass. Come join this vibrant community of macro investors, asset allocators and hedge funds – check out which subscription tier suits you the most using this link.