The recessionistas are now forced to look to the third quarter as the earliest start date for an economic downturn in the US.

The odds have been low recently that Q2 would mark the beginning of an NBER-defined contraction and yesterday’s stronger-than-expected rise in output for the April-through-June period seals the deal.

US economic activity rose 2.8% in Q2, well above the consensus forecast and CapitalSpectator.com’s final nowcast for the previous quarter.

Despite the news, a certain segment of the economics community will remain undaunted in predicting that a recession is near. Fear springs eternal, you might say for this crowd.

They’ll be right, eventually. However, the flawed methodologies that dominate most recession analytics ensure that the doomsters will usually be on the back foot for anticipating the start of the next downturn.

The two main errors that trip up many (most?) recession estimates: are excessive reliance on a small number of indicators and/or looking too far into the future.

I’ve written extensively on these and related oversights over the years (see here and here, for recent examples).

The antidote: a diversified, multi-factor approach to modeling recession risk (per the methodology in the weekly updates of The US Business Cycle Risk Report).

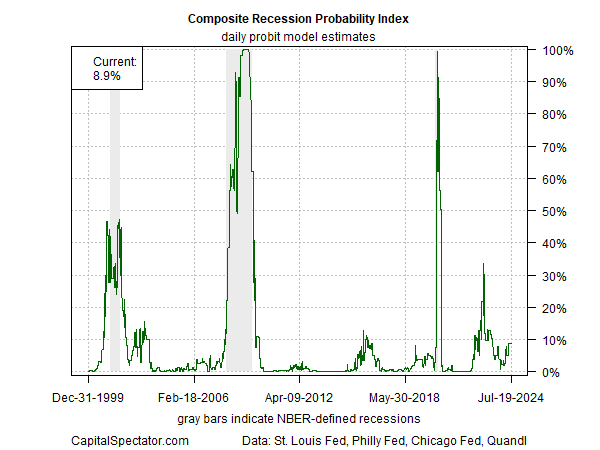

On that score, this approach continues to reflect a low probability that a downturn has started or is imminent.

Consider that the newsletter’s main recession indicator, which aggregates several business-cycle indexes, was estimating a downturn probability of roughly 9% before yesterday’s Q2 report was published.

It’s fair to assume that this low probability will remain more or less steady after the GDP report.

Despite the latest Q2 report, the analysts who’ve recently been predicting a recession is near/imminent will remain undaunted.

A quick look at some post-GDP-release comments shows that the recession forecasts have simply been moved forward once more.

In time, the forecast will be accurate, in the same way that a broken clock will eventually reflect the correct time. But in the pursuit of practical, real-world analytics, this is no way to run a railroad.

Fortunately, there’s a better way to estimate/nowcast recession risk, and it starts by recognizing that you can’t reliably model conditions much beyond a 2-3 month window into the future.

Meantime, cherry-picking indicators and/or falling into the trap of relying (intentionally or otherwise) on behavioral influences to inform your view has proven, again and again, to be a failed approach.

On the other hand, it does attract a crowd in the media, which is probably why deeply flawed recession analytics remain so popular.