ozgurdonmaz/iStock Unreleased via Getty Images

Introduction

I don’t know about you, but I love annual reports much more than quarterly ones. They give a better and more balanced picture of what actually happened through a significant amount of time. Recently, Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) released it Q4 earnings and this means there is a new 10-K to look at.

Many things can be said about Apple. One of the most intriguing and less researched consists in assessing Apple’s road towards cash neutrality. With a new 10-K available, it is now time to look at what happened in the past year and see what new steps the company has made.

The Goal Of Cash Neutrality

Last year, I published a first article on cash neutrality, trying to show what Apple was aiming at. In summary, we have to recall how a few years ago Apple started to deal with an issue that many may actually see as a non-existent one: the company was sitting on an enormous pile of unused cash, even after funding its operations and its investments. When this happens, a company needs to decide what to do with this excess cash. Why? Because just holding onto huge masses of liquidity without knowing what to do with it can be costly, both in terms of management and in terms of value erosion due to inflation.

The problem became even greater after 2018. Before then, Apple held most of its cash outside the U.S. in its foreign subsidiaries. This was done to avoid repatriation taxes. When the U.S. approved a tax reform bill with a 15.5% repatriation tax rate, Apple repatriated $250 billion. This was reported in early 2018. Soon thereafter, Apple disclosed that it would become a cash neutral company.

In Apple’s Q1 2018 earnings call, Luca Maestri, Apple’s CFO, explained this new goal with the following words:

Tax reform will allow us to pursue a more optimal capital structure for our company. Our current net cash position is $163 billion. And given the increased financial and operational flexibility from the access to our foreign cash, we are targeting to become approximately net cash neutral over time. We will provide an update to our specific capital allocation plans when we report results for our second fiscal quarter, consistent with the timing of updates that we have provided in the past.

Tim Cook, on the same call, provided a simple explanation to Mr. Maestri’s words: “What Luca is saying is not cash equals zero. He’s saying there’s an equal amount of cash and debt and that they balance to zero”.

Why is this necessary?

These words were needed because many analysts during the call seemed to misunderstand the idea of cash neutrality and thought, at first, that Apple was going to get rid of its cash balance until it went to zero.

When a corporation grows larger and becomes so profitable it generates pile of cash, it needs to decide what to do with this money. Since 2018, Apple, for example, has hiked its dividend while also deploying a lot of money for share repurchases.

Apple’s Goal Is Hindered By Apple’s Itself

However, as we will see in the rest of this article, although Apple’s endeavor appears clear, it should not be assumed it will be reached soon, unless a major change happens. In fact, Apple keeps on throwing out cash and distributing it to its shareholders while it is still far away from reaching a cash neutral position.

During the last earnings call, Apple’s Maestri, pointed out the progress of Apple’s cash neutrality policy with the following words:

Let me now turn to our cash position and capital return program. We ended the quarter with over $162 billion in cash and marketable securities. We increased commercial paper by $2 billion, leaving us with total debt of $111 billion. As a result, net cash was $51 billion at the end of the quarter. And our goal of becoming net cash-neutral over time remains unchanged. During the quarter, we returned nearly $25 billion to shareholders, including $3.8 billion in dividends and equivalents and $15.5 billion through open market repurchases of 85 million Apple shares. We also began a $5 billion accelerated share repurchase program in August, resulting in the initial delivery and retirement of 22 million shares.

As we can see, becoming cash neutral is strictly linked to shareholder distributions, such as dividends and share repurchases.

But, before we move on, we should be aware of how Apple considers its cash and its debt positions. In fact, if we look at Apple’s financials available on Seeking Alpha, we don’t find the same numbers Mr. Maestri talked about. For example, Mr. Maestri speaks about $162 billion in cash and marketable securities, but we only find $29.965 billion in cash and cash equivalents with another $31.59 billion in short-term investments. The sum of the two doesn’t even make up a half of Apple’s disclosed cash position. This is because Apple considers as part of its cash its long-term marketable securities. At the end of the last fiscal year, Apple had over $100 billion in long-term marketable securities.

Apple’s debt is accounted for in a similar way: it is made up of commercial paper, short-term borrowings and long-term debt.

Let’s take a look at Apple’s progress since the company announced its cash neutral policy.

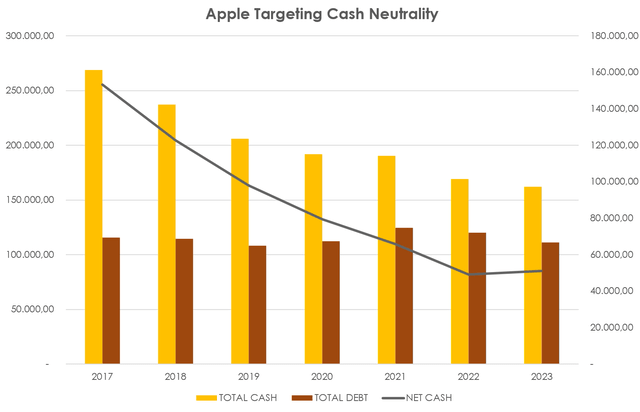

Author, with data from Apple’s Form 10-Ks

The trend is clear: Apple has been able to cut its cash position in half, while keeping its debt pretty much stable between $110 and $120 billion. What does this mean? Apple is not targeting cash neutrality not so much by raising its debt but rather by reducing its cash balance.

How does Apple do that? Dividends and share repurchases. Actually, because of the huge impact Apple’s share buybacks have on the number of outstanding shares, the company pretty much pays the same amount each year in dividends (around $15 billion).

Now, while Apple tries to bring its cash balance down, there is an intrinsic part of its business that makes up a real brake to this process. I am speaking of Apple’s cash flow generation. Every year, Apple generates billions in free cash flow which, if not used nor invested, increase the cash balance.

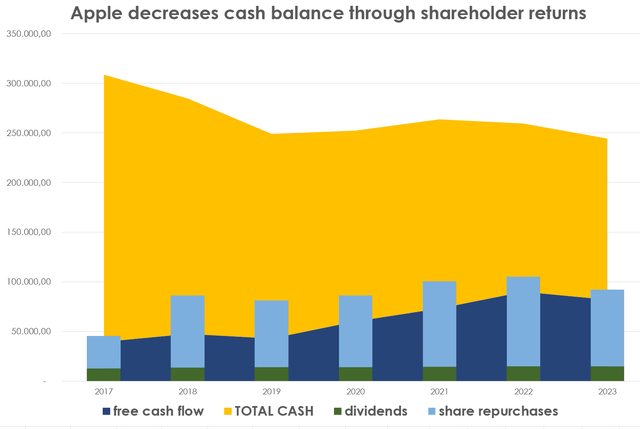

The graph below tries to show what I am talking about. The yellow area shows Apple’s total cash position since 2017. As we can see, it doesn’t trend downwards with the same trajectory of the line in the graph below. Why is that? Because the yellow area is supported by the growing blue area, which represents the yearly free cash flow of Apple. This increases and thus supports Apple’s cash position in a very strong way.

The graph also shows how Apple is returning money to its shareholders. The green base of each column shows Apple’s dividends, which are pretty much stable. The light blue column shows Apple’s buybacks. The sum of the two has been greater than Apple’s yearly free cash flow generation. This is necessary because, if Apple wants to reduce its cash balance, it needs to pay out more than its free cash flow. However, we can see how rapidly free cash flow grows to the extent the company is almost having a hard time reducing its cash position.

Author, with data from Apple’s Form 10-Ks

As I showed last year, Apple will probably reach cash neutrality between 2025 and 2026. But, by then, its free cash flow generation will be so strong that Apple will be forced to meaningfully increase its buybacks if it wants to stay cash neutral over time. This is why there is no reason to believe buybacks will stop once Apple has become cash neutral.

In particular, free cash flow is growing because Apple’s installed-base of active devices is over two billion. As a consequence, Apple’s paid subscriptions are growing and are now over one billion (almost twice the amount seen just three years ago). This explains why services revenue is setting all-time records year after year. Just in 2023, it topped $85 billion and just in Q4 it grew 16% YoY. We are talking about a business line with 70.9% gross margin. So, while Apple strives to push down its cash balance, there is a force pushing cash up: a true buoyancy opposing to a gravitational force. And this is all happening organically within Apple.

Does this mean Apple won’t reach its goal? I don’t think so. Once Apple commits itself to doing something, it usually works its way around every issue. In this case, I see a very simple (and pleasant solution). Apple’s massive buybacks won’t stop but will actually have to increase and surpass the $100 billion threshold soon, without, of course, stopping there.