So, we are back to the argument about whether we have reached a new era of permanently higher growth and earnings, and because of productivity also a permanent state of steady disinflationary pressures.

Live long enough, and you’ll see this argument come around a couple of times. In the late 60s with the “Nifty Fifty” stocks, in the 1990s with the Internet, and now with AI. As a first pass, it’s worth noting as an equity investor that the first two of those eras were followed by long periods of flat to negative real returns in equities. But my purpose here is simply to revisit the important fact that productivity is always improving, so something which improves productivity is normal and not exciting. The question which arises periodically when we see some really golly-gee-whiz innovation is whether that innovation can meaningfully accelerate the rate of productivity growth over time.

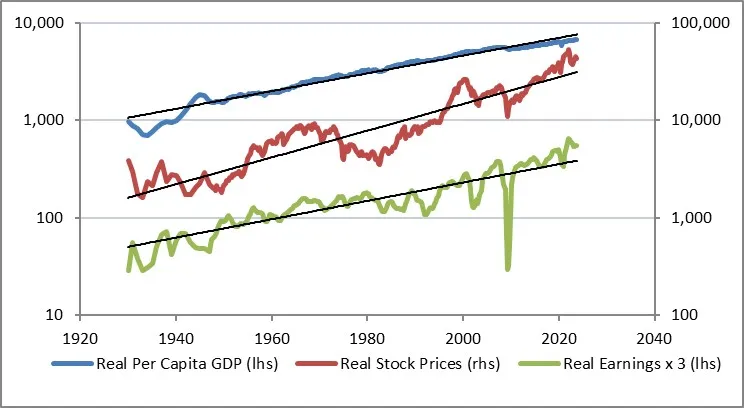

Total real growth over time is simply the growth in the labor force, plus the growth in output per hour (productivity). Assuming that the labor force grows at roughly the same rate as the overall population,[1] real GDP per capita should grow at roughly the rate of productivity. The chart below extends a chart which first appeared in an article by Brad Cornell and Rob Arnott in 2008 (“The ‘Basic Speed Law’ for Capital Markets Returns“), updated to the end of 2023Q3. Note that real earnings and real GDP grow at almost the same rate over time – the log regression slope is 2.09% for real per capita and 2.17% for real earnings.

(By the way, although it isn’t part of my discussion here note that the middle line, real stock prices, isn’t parallel. It was, back when this chart first appeared in 2008; the fact that it isn’t anymore is obviously attributable to increases in valuation multiples over a long period of time. Discuss.)

A permanent (or at least long-lived) increase in the long-run rate of productivity growth, then, would be massively important. It would mean that GDP per capita – standard of living, in other words – would rise at a permanently faster pace. This is the crux of the question, as I said above and as NY Fed President John Williams said in an interview with Axios a few days ago (ht Alex Manzara):

“One way to think of it is AI is – and this is my own, but based on what I heard from others – is AI is just that new thing that’s going to get us that 1% to 1.5% productivity growth that we’ve been getting for decades or even a century.

“It’s the thing that gets us that, just like computers did or other changes in technology and how we produce things in the economy. So it’s just the thing that gets us that 1% to 1.5% productivity growth.

“The other view, which I think has some support, is AI is more of a general purpose technology. …So there is a possibility that we could get a decade or more faster productivity growth if this really is its general purpose and revolution. You can’t exclude that.”

What Williams said, about AI being a “general purpose technology” that spurs faster productivity growth for a decade or more, is something that we honestly have a pretty good history of. The explosion of the internet into general use in the late 1990s triggered an equity market bubble that eventually popped. Greenspan mused, in late 1996, that it’s hard to tell when stock prices reflect “irrational exuberance” and in February 1997 he said “history counsels caution” because “…regrettably, history is strewn with visions of such ‘new eras’ that in the end have proven to be a mirage.”

Was it a mirage? There is no question, a quarter-century later, that the internet has completely changed almost everything about the way that we live and work. If there was ever a ‘general purpose’ technology that led to a sustained long-term increase in productivity, the Internet is it.

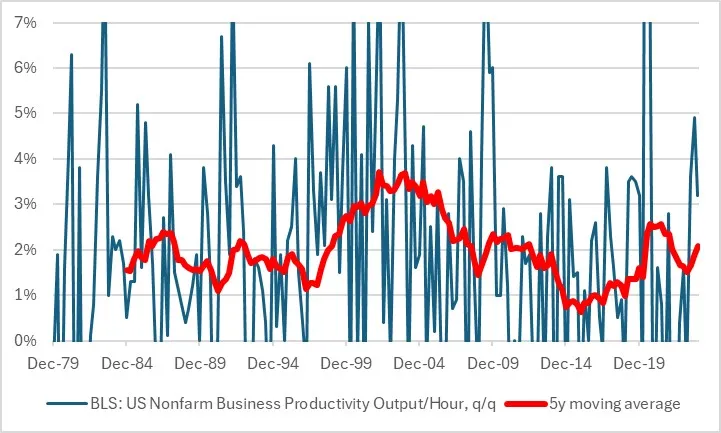

My next chart only goes back to 1979. It shows US Nonfarm Business Productivity, calculated quarterly by the BLS as part of the GDP report. Obviously, the quarterly numbers are incredibly volatile – so much so, in fact, that I’ve truncated a large portion of the tails. It’s devilishly hard to measure productivity. More on that in a moment. The red line is the 20-quarter (5-year) moving average. The average over the whole period is…surprise!…1.92%, very close to the average increase in real earnings and real GDP per capita. As I said before, that’s what we expected to find.

But there is certainly a bulge in the chart. Noticeably, it doesn’t happen until long after the internet hype had crested, but it is definitely there. The average on this chart from 1979-1998 is 1.78%, and the average since 2005 is 1.59%. But the average from 1999-2005 inclusive is a whopping 3.11%. An acceleration of productivity growth of 1.4% or so, for 7 years, means that our standard of living moved permanently higher by about 10% during that period, over and above what it would have done anyway.

That’s meaningful. I would also argue that it’s probably the upper limit of what we should expect from the AI revolution. Starting in few years, if this is a “general purpose technology” advancement, we could conceivably see growth accelerate by 1.5% per year for some part of a decade. Let’s all hope that happens, because that 10% total growth is the real growth – it is extra growth without any extra inflation. A free lunch, as it were. I say that’s probably the rough upper limit because I can’t imagine how the AI revolution could possibly be more impactful than the internet revolution was, or any of the other major technology revolutions we have seen over the past century.

That’s the good news. If this is real, it would be a wonderful thing and there’s some historical evidence that when the market gets excited like this, it might not be entirely a mirage. Now the bad news. If this is an internet-style leap forward, the aggregate incremental increase in real earnings we should expect compared with the normal trend is…10%. Not a doubling, or tripling, but 10%. Naturally, those gains will accrue to a smaller subset of companies at first, but the other lesson of the internet boom is that those gains eventually percolate around because that’s the whole point of a “general purpose technology.”

Have we gotten our 10% yet? Seems like maybe we have.

[1] This assumption is clearly false, but it’s false in transparent ways. Right now, the population is growing faster than the labor force due to immigration. As Baby Boomers retire, the labor force will grow more slowly than the population. Etc. The assumption here is not meant to be uniformly and universally true, but approximately true on average so as to make the general point which follows. To the extent that this assumption is transparently incorrect, we know how to adjust the general point which follows, for the specific conditions.

Visit my blog here to read all my articles.